Let me take you under the bonnet of a TV news report I watched a couple of days ago. (You can watch it for yourself here. )

Let me deconstruct it, to reveal the care and thought that had gone into its construction.

And let me leave you with five tips on how you can make potentially boring-but-important things compelling to your staff and stakeholders, clients and customers — whether you’re preparing a report for the Board, a tricky meeting with your teams, or a do-or-die sales pitch.

The example that caught my eye is a news report broadcast on BBC News on the eve of the COP26 conference in Glasgow. The reporter’s job was to explain why it mattered — before his audience tuned out.

Here’s how I believe David Shukman, the BBC’s Science Editor, succeeded.

1: COMPELLING PICTURES

The report opened with the sight – and sound – of mud being clawed from the earth, with crude tools and bare hands, to hold back the sea. You could almost smell it.

When you make a presentation with slides, how often do you use a real image that resonates? Do you use a real image at all? Or do you make do with some facts and figures in the correct font, or a random stylised image grabbed from Google?

2. A TIGHT SCRIPT

The opening three sentences are simple and crisp. One of them is only four words long.

“In a village on the coast of Bangladesh, people are using mud to hold back the sea. It’s all they’ve got. The rising levels of the ocean mean they’re being flooded more often.”

When your fingers hover over the keyboard, how often do you think about the length of the sentences you are going to write? I don’t do it as often as I should, now that my days as a BBC News reporter are over. But analysing this news report has reminded me that less is so often more.

3. ONE PERSON’S STORY FIRST

It takes the reporter only 48 seconds before he hones in on one person’s story to illustrate the global challenge. You might call her the ‘case-study’: it’s a phrase we often use in news, too. We see pictures of Shorbanu Khatun, in saffron robes, repairing what appears to be her home, a low dark hut.

When you want to have an impact with your audience, what information do you share first? The data? Or the stories — the ‘case-studies’ — about the people who are affected by the data?

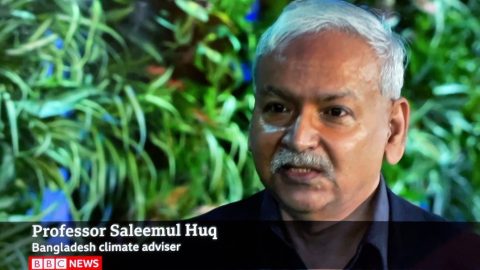

4. THE EXPERT SECOND

We hear Ms Khatun’s story — and how she feels let down by the unfulfilled promises from the COP 15 summit in Copenhagan twelve years ago. We see her around her cooking pot on a dusty floor. The story continues with images of sandbags, a new school, fresh water: evidence that things are at least improving. And only then — the second voice, not the first — do we hear from the expert, a professor, to provide the analysis.

If you’re the expert called upon to make the presentation or deliver the pitch, how often do you put your expertise second … behind the story of the ‘case study’?

5. SO MUCH LEFT OUT

David Shukman’s entire news report lasts 2 minutes and 31 seconds. Of this, the soundbite with Ms Khatun lasts 14 seconds, the soundbite with the professor lasts 12 seconds. I suspect each of the interviews had lasted at least five minutes — possibly much longer. But the reporter’s greatest skill is deciding what must be left out, whilst preserving the integrity and the truth.

When you’re preparing a presentation, do you include as much as you can, because you believe that is what your audience wants? Or do you realise that what your audience wants is for you to spare them too much detail, keep things simple — and leave them with a story that they will remember and act upon?

————————

I realise, of course, that this formula does not work in every scenario. Facts and data, boring though they may be, matter — especially in business and sales.

But TV News is a discipline that works in tandem with other forms of news. News bulletins will often encourage viewers to go to news web pages for links where more details, statistics and tables can be found and digested more easily.

In a presentation of your own, providing links to documents or websites may be a better use of your time ‘on air’ than trying to tear through it. Next time you’re making a case, in a time-limited form, to an impatient audience, be sure to tell them where they can pore over the data at their own pace.

But reassure them that but because you know their time is precious, as you stand before them, you’re simply going to tell them — and show them — a story that they will remember.

If you’d like some help finding the stories in your business … working out what to include, and what can be left out … do get in touch.